The connected and disconnected layers of ADO.NET provide you with a fabric that lets you select, insert, update, and delete data with connections, commands, data readers, data adapters, and DataSet objects. While this is all well and good, these aspects of ADO.NET force you to treat the fetched data in a manner that is tightly coupled to the physical database schema. Recall for example, that when you use the connected layer, you typically iterate over each record by specifying column names to a data reader. On the other hand, if you opt to use the disconnected layer, you find yourself traversing the rows and columns collections of a DataTable object within a DataSet container.

If you use the disconnected layer in conjunction with strongly typed DataSets/data adapters, you end up with a programming abstraction that provides some helpful benefits. First, the strongly typed DataSet class exposes table data using class properties. Second, the strongly typed table adapter supports methods that encapsulate the construction of the underlying SQL statements. Recall the AddRecords() method from Chapter 22:

public static void AddRecords(AutoLotDataSet.InventoryDataTable tb, InventoryTableAdapter dAdapt) { // Get a new strongly typed row from the table. AutoLotDataSet.InventoryRow newRow = tb.NewInventoryRow(); // Fill row with some sample data. newRow.CarID = 999; newRow.Color = "Purple"; newRow.Make = "BMW"; newRow.PetName = "Saku"; // Insert the new row. tb.AddInventoryRow(newRow); // Add one more row, using overloaded Add method. tb.AddInventoryRow(888, "Yugo", "Green", "Zippy"); // Update database. dAdapt.Update(tb); }

Things get even better if you combine the disconnected layer with LINQ to DataSet. In this case, you can apply LINQ queries to your in-memory data to obtain a new result set, which you can then optionally map to a standalone object such as a new DataTable, a List<T>, Dictionary<K,V>, or array of data, as follows:

static void BuildDataTableFromQuery(DataTable data) { var cars = from car in data.AsEnumerable() where car.Field<int>("CarID") > 5 select car; // Use this result set to build a new DataTable. DataTable newTable = cars.CopyToDataTable(); // Work with DataTable... }

LINQ to DataSet is useful; however, you need to remember that the target of your LINQ query is the data returned from the database, not the database engine itself. Ideally, you could build a LINQ query that you send directly to the database engine for processing, and get back some strongly typed data in return (which is exactly what the ADO.NET Entity Framework lets you accomplish).

When you use either the connected or disconnected layer of ADO.NET, you must always be mindful of the physical structure of the back-end database. You must know the schema of each data table, author complex SQL queries to interact with said table data, and so forth. This can force you to author some fairly verbose C# code because as C# itself does not speak the language of database schema directly.

To make matters worse, the way in which a physical database is constructed (by your friendly DBA) is squarely focused on database constructs such as foreign keys, views, and stored procedures. The databases constructed by your friendly DBA can grow quite complex as the DBA endeavors to account for security and scalability. This also complicates the sort of C# code you must author in order to interact with the data store.

The ADO.NET Entity Framework (EF) is a programming model that attempts to lessen the gap between database constructs and object-oriented programming constructs. Using EF, you can interact with a relational database without ever seeing a line of SQL code (if you so choose). Rather, when you apply LINQ queries to your strongly typed classes, the EF runtime generates proper SQL statements on your behalf.

Note LINQ to Entities is the term that describes the act of applying LINQ queries to ADO.NET EF entity objects.

Another possible approach: Rather than updating database data by finding a row, updating the row, and sending the row back for processing with a batch of SQL queries, you can simply change properties on an object and save its state. Again, the EF runtime updates the database automatically.

As far as Microsoft is concerned, the ADO.NET Entity Framework is a new member of the data access family, and it is not intended to replace the connected or disconnected layers. However, once you spend some time working with EF, you might quickly find yourself preferring this rich object model over the more primitive world of SQL queries and row/column collections.

Nevertheless, chances are you will find uses for all three approaches in your .NET projects; in some cases, the EF model might complicate your code base. For example, if you want to build an in-house application that needs to communicate only with a single database table, you might prefer to use the connected layer to hit a batch of related stored procedures. Larger applications can particularly benefit from EF, especially if the development team is comfortable working with LINQ. As with any new technology, you will need to determine how (and when) ADO.NET EF is appropriate for the task at hand.

Note You might recall a database programming API introduced with .NET 3.5 called LINQ to SQL. This API is close in concept (and fairly close in terms of programming constructs) to ADO.NET EF. While LINQ to SQL is not formally dead, the official word from those kind folks in Redmond is that you should put your efforts into EF, not LINQ to SQL.

The strongly typed classes mentioned previously are called entities. Entities are a conceptual model of a physical database that maps to your business domain. Formally speaking, this model is termed an Entity Data Model (EDM). The EDM is a client-side set of classes that map to a physical database, but you should understand that the entities need not map directly to the database schema in so far as naming conventions go. You are free to restructure your entity classes to fit your needs, and the EF runtime will map your unique names to the correct database schema.

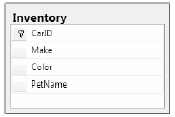

For example, you might recall that you created the simple Inventory table in the AutoLot database using the database schema shown in Figure 23-1.

Figure 23-1 Structure of the Inventory table of the AutoLot database

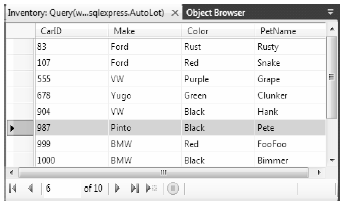

If you were to generate an EDM for the Inventory table of the AutoLot database (you’ll see how to do so momentarily), the entity will be called Inventory by default. However, you could rename this class to Car and define uniquely named properties of your choosing, which will be mapped to the columns of the Inventory table. This loose coupling means that you can shape the entities so they closely model your business domain. Figure 23-2 shows such an entity class.

Figure 23-2 The Car entity is a client-side reshaping of the Inventory schema

Note In many cases, the client-side entity class will be identically named to the related database table. However, remember that you can always reshape the entity to match your business situation.

Now, consider the following Program class, which uses the Car entity class (and a related class named AutoLotEntities) to add a new row to the Inventory table of AutoLot. This class is termed an object context; the job of this class it is to communicate with the physical database on your behalf (you will learn more details soon):

class Program { static void Main(string[] args) { // Connection string automatically read from // generated config file. using (AutoLotEntities context = new AutoLotEntities()) { // Add a new record to Inventory table, using our entity. context.Cars.AddObject(new Car() { AutoIDNumber = 987, CarColor = "Black", MakeOfCar = "Pinto", NicknameOfCar = "Pete" }); context.SaveChanges(); } } }

It is up to the EF runtime to take the client-side representation of the Inventory table (here, a class named Car) and map it back to the correct columns of the Inventory table. Notice that you see no trace of any sort of SQL INSERT statement; you simply add a new Car object to the collection maintained by the aptly named Cars property of the context object and save your changes. Sure enough, if you view the table data using the Server Explorer of Visual Studio 2010, you will see a brand new record (see Figure 23-3).

Figure 23-3 The result of saving the context

There is no magic in the preceding example. Under the covers, a connection to the database is made, a proper SQL statement is generated, and so forth. The benefit of EF is that these details are handled on your behalf. Now let’s look at the core services of EF that make this possible.

The EF API sits on top of the existing ADO.NET infrastructure you have already examined in the previous two chapters. Like any ADO.NET interaction, the entity framework uses an ADO.NET data provider to communicate with the data store. However, the data provider must be updated so it supports a new set of services before it can interact with the EF API. As you might expect, the Microsoft SQL Server data provider has been updated with the necessary infrastructure, which is accounted for when using the System.Data.Entity.dll assembly.

Note Many third party databases (e.g., Oracle and MySQL) provide EF-aware data providers. Consult your database vendor for details or log onto www.sqlsummit.com/dataprov.htm for a list of known ADO.NET data providers.

In addition to adding the necessary bits to the Microsoft SQL Server data provider, the System.Data.Entity.dll assembly contains various namespaces that account for the EF services themselves. The two key pieces of the EF API to concentrate on for the time being are object services and entity client.

Object services is the name given to the part of EF that manages the client-side entities as you work with them in code. For example, object services track the changes you make to an entity (e.g., changing the color of a car from green to blue), manage relationships between the entities (e.g., looking up all orders for a customer named Steve Hagen), and provide ways to save your changes to the database, as well as ways to persist the state of an entity with XML and binary serialization services.

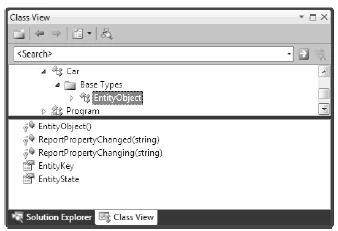

Programmatically speaking, the object services layer micromanages any class that extends the EntityObject base class. As you might suspect, EntityObject is in the inheritance chain for all entity classes in the EF programming model. For example, if you look at the inheritance chain of the Car entity class used in the previous example, you see that Car Is-A EntityObject (see Figure 23-4).

Figure 23-4 EF’s object service layer can manage any class that extends EntityObject

Another major aspect of the EF API is the entity client layer. This part of the EF API is in charge of working with the underlying ADO.NET data provider to make connections to the database, generate the necessary SQL statements based on the state of your entities and LINQ queries, map fetched database data into the correct shape of your entities, and manage other details you would normally perform by hand if you were not using the Entity Framework.

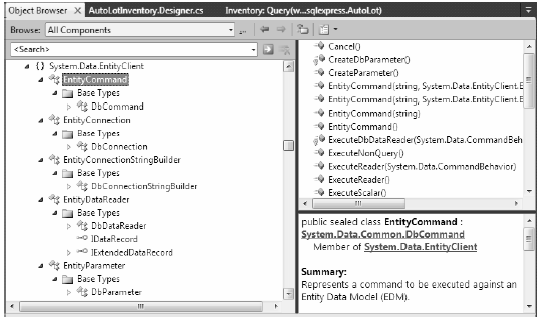

You can find the functionality of the entity client layer in the System.Data.EntityClient namespace. This namespace includes a set of classes that map EF concepts (such as LINQ to Entity queries) to the underlying ADO.NET data provider. These classes (e.g., EntityCommand and EntityConnection) are eerily similar to the classes you find in an ADO.NET data provider; for example, Figure 23-5 illustrates how the classes of the entity client layer extend the same abstract base classes of any other provider (e.g., DbCommand and DbConnection; you can also see Chapter 22 for more details on this subject).

Figure 23-5 The entity client layer maps entity commands to the underlying ADO.NET data provider

The entity client layer typically works behind the scenes, but it is entirely possible to work directly with an entity client if you require full control over how it performs its duties (most notably, how it generates the SQL queries and handles the returned database data).

If you require greater control over how the entity client builds a SQL statement based on the incoming LINQ query, you can use Entity SQL. Entity SQL is a database-independent dialect of SQL that works directly with entities. Once you build an entity SQL query, it can be sent directly to entity client services (or if you wish, to object services), where it will be formatted into a proper SQL statement for the underlying data provider. You will not work with Entity SQL to any significant extent in this chapter, but you will see a few examples of this new SQL-based grammar later in the chapter.

If you require greater control over how a fetched result set is manipulated, you can forego the automatic mapping of database results to entity objects and manually process the records using the EntityDataReader class. Unsurprisingly, the EntityDataReader allows you to process fetched data using a forward only, read only stream of data, just as SqlDataReader does. You will see a working example of this approach later in the chapter.

Recapping the story thus far, entities are client-side classes, which function as an Entity Data Model. While the client side entities will eventually be mapped to the correct database table, there is no tight coupling between the property names of your entity classes and the column names on the data table.

For the Entity Framework API to map entity class data to database table data correctly, you need a proper definition of the mapping logic. In any data model-driven system, the entities, the real database, and the mapping layers are separated into three related parts: a conceptual model, a logical model, and a physical model.

In the world of EF, each of these three layers is captured in an XML-based file format. When you use the integrated Entity Framework designers of Visual Studio 2010, you end up with a file that takes an *.edmx file extension (remember, EDM = entity data model). This file includes XML descriptions of the entities, the physical database, and instructions on how to map this information between the conceptual and physical models. You will examine the format of the *.edmx file in the first example of this chapter (which you will see in a moment).

When you compile your EF-based projects using Visual Studio 2010, the *.edmx file is used to generate three standalone XML files: one for the conceptual model data (*.csdl), one for the physical model (*.ssdl), and one for the mapping layer (*.msl). The data of these three XML-based files is then bundled into your application in the form of binary resources. Once compiled, your .NET assembly has all the necessary data for the EF API calls you make in your code base.

The final part of the EF puzzle is the ObjectContext class, which is a member of the System.Data.Objects namespace. When you generate your *.edmx file, you get the entity classes that map to the database tables and a class that extends ObjectContext. You typically use this class to interact with object services and entity client functionality indirectly.

ObjectContext provides a number of core services to child classes, including the ability to save all changes (which results in a database update), tweak the connection string, delete objects, call stored procedures, and handle other fundamental details. Table 23-1 describes some of the core members of the ObjectContext class (be aware that a majority of these members stay in memory until you call SaveChanges()).

Table 23-1. Common Members of ObjectContext

| Member of ObjectContext | Meaning in Life |

|---|---|

| AcceptAllChanges() | Accepts all changes made to entity objects within the object context. |

| AddObject() | Adds an object to the object context. |

| DeleteObject() | Marks an object for deletion. |

| ExecuteFunction<T>() | Executes a stored procedure in the database. |

| ExecuteStoreCommand() | Allows you to send a SQL command to the data store directly. |

| GetObjectByKey() | Locates an object within the object context by its key. |

| SaveChanges() | Sends all updates to the data store. |

| CommandTimeout | This property gets or sets the timeout value in seconds for all object context operations. |

| Connection | This property returns the connection string used by the current object context. |

| SavingChanges | This event fires when the object context saves changes to the data store. |

The ObjectContext derived class serves as a container that manages entity objects, which are stored in a collection of type ObjectSet<T>. For example, if you generate an *.edmx file for the Inventory table of the AutoLot database, you end up with a class named (by default) AutoLotEntities. This class supports a property named Inventories (note the plural name) that encapsulates an ObjectSet<Inventory> data member. If you create an EDM for the Orders table of the AutoLot database, the AutoLotEntities class will define a second property named Orders that encapsulates an ObjectSet<Order> member variable. Table 23-2 defines some common members of System.Data.Objects.ObjectSet<T>.

Table 23-2. Common members of ObjectSet<T>

| Member of ObjectSet<T> | Meaning in Life |

|---|---|

| AddObject() | Allows you to insert a new entity object into the collection. |

| CreateObject<T>() | Creates a new instance of the specified entity type. |

| DeleteObject | Marks an object for deletion. |

Once you drill into the correct property of the object context, you can call any member of ObjectSet<T>. Consider again the sample code shown in the first few pages of this chapter:

using (AutoLotEntities context = new AutoLotEntities()) { // Add a new record to Inventory table, using our entity. context.Cars.AddObject(new Car() { AutoIDNumber = 987, CarColor = "Black", MakeOfCar = "Pinto", NicknameOfCar = "Pete" }); context.SaveChanges(); }

Here, AutoLotEntities is-a ObjectContext. The Cars property gives you access to the ObjectSet<Car> variable. You use this reference to insert a new Car entity object and tell the ObjectContext to save all changes to the database.

ObjectSet<T> is typically the target of LINQ to Entity queries; as such, ObjectSet<T> supports the same extension methods you learned about in Chapter 13. Moreover, ObjectSet<T> gains a good deal of functionality from its direct parent class, ObjectQuery<T>, which is a class that represents a strongly typed LINQ (or Entity SQL) query.

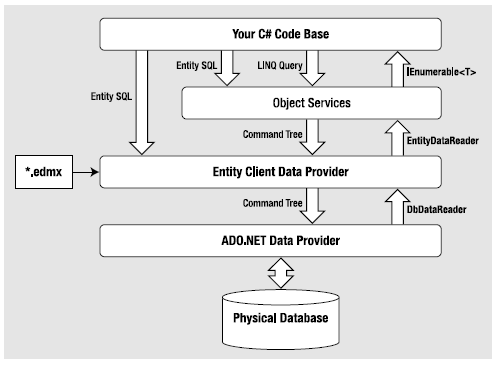

Before you build your first Entity Framework example, take a moment to ponder Figure 23-6, which shows you how the EF API is organized.

Figure 23-6 The major components of the ADO.NET Entity Framework

The moving parts illustrated by Figure 23-6 are not as complex as they might seem at first glance. For example, consider this common scenario. You author some C# code that applies a LINQ query to an entity you received from your context. This query is passed into object services, where it formats the LINQ command into a tree entity client can understand. In turn, the entity client formats this tree into a proper SQL statement for the underlying ADO.NET provider. The provider returns a data reader (e.g., a DbDataReader derived object) that client services use to stream data to object services using an EntiryDataReader. What your C# code base gets back is an enumeration of entity data (IEnumerable<T>).

Here is another scenario to consider. Your C# code base wants more control over how client services constructs the eventual SQL statement to send to the database. Thus, you author some C# code using Entity SQL that can be passed directly to entity client or object services. The end result returns as an IEnumerable<T>.

In either of these scenarios, you must make the XML data of the *.edmx file known to client services; this enables it to understand how to map database atoms to entities. Finally, remember that the client (e.g., your C# code base) can also nab the results sent from entity client by using the EntityDataReader directly.